Prepared by the Honourable A. Anne McLellan, P.C., O.C., A.O.E

June 28, 2019

Table of Contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- The current Canadian framework

- Evaluating the current model

- A proposed Canadian approach to the role of the Attorney General

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Biographies

- Appendix B: Consultation participants

- Appendix C: Sources

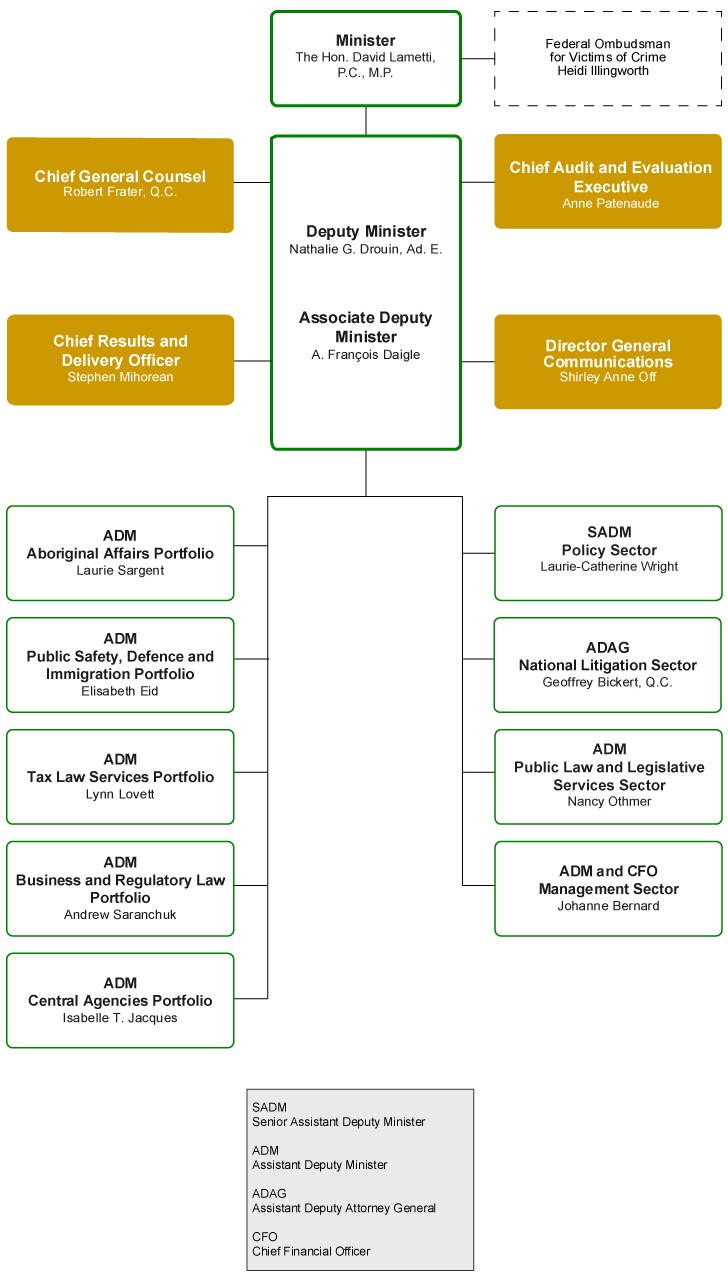

- Appendix D: Organization of the Department of Justice Canada

- Appendix E: Attorneys General in common law countries

Executive summary

On March 18, 2019, the Prime Minister of Canada appointed me to be his Special Advisor on the roles of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada.

He asked me to:

- Assess the structure which has been in place since Confederation of having the roles of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada held by the same person, to determine whether there should be any legislative or operational changes to this structure; and,

- Review the operating policies and practices across the Cabinet, and the role of public servants and political staff in their interactions with the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada.

To carry out this mandate, I consulted with a broad range of experts. These experts included academics, former and current government officials, political staff, lawyers, officials and academics in the United Kingdom and Australia, and most of the Attorneys General of Canada from the past twenty-five years.

I also reviewed the literature on the role of the Attorney General in Canada and elsewhere.

It is clear to me that there is no system for managing prosecutorial decisions that absolutely protects against the possibility of partisan interference, while providing for public accountability.

I do not believe that further structural change is required in Canada to protect prosecutorial independence and promote public confidence in the criminal justice system. Legislation, education, protocols, cultural norms, constitutional principles and public transparency all play a role. The Director of Public Prosecutions Act provides strong structural protections against political interference. The personal integrity of the Attorney General is also essential; indeed, it is probably the most important element in a system which protects the rule of law.

The model of having the same person hold the Minister of Justice and Attorney General roles was deliberately chosen at Confederation, and for good reason. Our system benefits from giving one person responsibility for key elements of the justice system. Joinder of the roles creates important synergies. That person gains a perspective over the entire system which could not be achieved if the roles were divided; so too do the lawyers and policy experts who work together in the Department of Justice.

Removing the Attorney General from Cabinet would also affect the credibility and quality of legal advice they provide.[1] In my view, Cabinet colleagues are more likely to pay attention to the Attorney General’s legal advice because they know that the Attorney General, as a member of Cabinet, understands the political context in which they are operating. That advice is also likely to be better informed, and therefore more helpful to Cabinet.

I believe that any concerns about the joined roles can be addressed through a comprehensive protocol on ministerial consultations on the public interest; an education program for ministers and others on the role of the Attorney General and related issues; a new oath of office for the Ministry of Justice and Attorney General of Canada which recognizes the unique role of the Attorney General; and changes to the Department of Justice Act, the federal prosecutors’ manual, and Open and Accountable Government, the guide for Cabinet ministers on their roles and responsibilities.

Recommendations:

- I recommend that the Attorney General of Canada develop a detailed protocol to govern ministerial consultations in specific prosecutions. This protocol should apply to ministers, their staff, the Office of the Clerk of the Privy Council and the public service. The protocol should address the following issues:

- Who is entitled to initiate consultations;

- Who determines the process for such consultations;

- When and where the consultations take place;

- Who is entitled to be part of the consultation discussions;

- What the scope of the discussion should be; and

- The Attorney General’s options and obligations in response to such consultations.

I have provided advice on the details of this protocol in my report.

- I recommend that the Public Prosecution Service of Canada Deskbook and the 2014 Directive on Section 13 notices contained within it be updated to clarify the following:

- Section 13 notices are privileged;

- The Attorney General may share Section 13 notices with the Deputy Minister of Justice or others to obtain advice on whether they should exercise their authority to issue a directive or take over a prosecution, without affecting the privileged status of the notices;

- The Attorney General may seek additional information from the Director of Public Prosecutions upon receiving a section 13 notice; and

- The Attorney General may issue specific directives or take over a prosecution on public interest grounds or because they are of the view that there is no reasonable prospect of conviction.

- I recommend that Attorneys General be encouraged to explain their reasons when issuing a direction or taking over a prosecution, or when declining to do so, in cases which raise significant public interest. How and when they do so will be context-dependent.

- I recommend the creation of two education programs. All parliamentarians should receive education on the role of the Attorney General. In addition, the Prime Minister should ensure that Cabinet members, their staff, and other relevant government officials receive more intensive training, including requiring participants to work through case examples. This education should also be provided to new ministers and staff following Cabinet shuffles or changes in staff. This education should address:

The role of each participant in protecting and promoting the rule of law;

The unique position of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada;

The roles of the Attorney General, the Director of Public Prosecutions, and individual prosecutors, particularly with respect to their independence in decision-making about specific prosecutions;

The consequences of interfering with prosecutorial discretion; and

The proper approach to consulting with the Attorney General of Canada and Director of Public Prosecutions with respect to the public interest involved in a specific prosecution.

- I recommend that Open and Accountable Government be amended as follows:

The discussion of the rule of law and the unique role of the Attorney General, including their obligations with respect to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and their independence when making prosecutorial decisions, must be front and centre.

It should be made clearer that virtually all prosecutorial decisions are made by the Director of Public Prosecutions and their designated agents, without any involvement by the Attorney General.

It should also be emphasized that while the Attorney General has the power to issue directions in specific cases or take over a prosecution, this power is exercised only in exceptional cases, and in fact has never been used at the federal level.

It should also be explained that in order to protect prosecutorial independence and ensure political accountability, the exercise of such powers by the Attorney General must by law be done transparently through a public, written notice which is published in the Canada Gazette. It is expected that the Attorney General would be answerable to Parliament for exercising these powers.

The current description of ministerial consultations should be replaced with the protocol I recommend.

- I recommend that the oath of office of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada be changed to refer specifically to the Attorney General’s unique role in upholding the rule of law, giving independent legal advice, and making decisions about prosecutions independently.

- I recommend that the Department of Justice Act be amended to make explicit the constitutional independence of the Attorney General in the exercise of their prosecutorial authority, confirm that their legal advice to Cabinet must be free of partisan considerations, and make explicit that these obligations take precedence over their other duties.

- I recommend that the title of the Department of Justice Canada be changed to the Department of Justice and Office of the Attorney General of Canada. The title of the Department of Justice Act should also reflect this change.

Introduction

Since Confederation, the person holding the position of Minister of Justice in the federal government has also held the position of Attorney General of Canada. The Attorney General of Canada has a unique and profoundly important role. They stand at the heart of accountable government as the person responsible for defending the rule of law by ensuring that all government action is in accordance with the Constitution, including the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In light of that responsibility, and in light of public concern about our system’s ability to protect against possible prosecutorial interference, the Prime Minister appointed me to be his Special Advisor on the roles of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada.

The Prime Minister asked me to:

- Assess the structure which has been in place since Confederation of having the roles of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada held by the same person, to determine whether there should be any legislative or operational changes to this structure; and,

- Review the operating policies and practices across the Cabinet, and the role of public servants and political staff in their interactions with the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada.

I have conducted this review with a number of considerations in mind:

First, I am not undertaking an inquiry into the SNC Lavalin matter. However, I am mindful that I have been given this mandate due to a perceived absence of clarity about the relationship between the government and the Attorney General and Minister of Justice in that matter. Therefore, my primary focus will be on issues affecting criminal prosecutions. Recognizing that the Attorney General and Minister of Justice have responsibilities beyond prosecutions, I will comment on these other functions as well.

Second, I am providing policy and government organization advice to the Prime Minister on the two questions he asked me to examine, rather than a detailed legal study.

Third, different jurisdictions have chosen different approaches to organize the functions of Attorneys General and Ministers of Justice. These reflect the history, politics and legal cultures of these jurisdictions. It is not advisable to simply transplant one model into a different context.

Fourth, all governments reorganize functions of government departments from time to time to meet evolving requirements. It must be recognized, however, that such changes have costs in terms of effectiveness. They can take a number of years to be fully implemented. They should be undertaken with a clear sense of what the proposed change can be expected to achieve.

Fifth, with the creation of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) in 2006, the federal justice system has undergone the most significant organizational change in the last half century.[2] My consultations have shown that there is a high degree of satisfaction with the separate prosecution organization which is now independent of the Department of Justice. My recommendations are intended to work with the DPP model.

Sixth, I believe that any proposals for change should be measured against the following objectives:

- Do they reinforce the independence of the prosecution function and the perception of independence?

- Do they provide clarity on roles and responsibilities in relation to prosecutions?

- Do they enhance a system of government that promotes the rule of law?

Finally, I believe it is important to examine a range of instruments available to assist in achieving these objectives, including organizational, legislative, policy, and educational reforms.

To help me with this review, I brought together a small team: a former Deputy Minister of Justice of Canada; a former Associate Deputy Minister of Justice of Canada with expertise on the role of the Attorney General; and a lawyer who has experience with reviews relating to the administration of justice. Their biographies are in Appendix A.

I also decided that before making any recommendations, I needed to consult broadly. My team and I spent several weeks speaking to law professors, political scientists, former and current federal and provincial government officials, political staff, lawyers, and other experts who generously shared their time and wisdom with us. Included in this large group of experts were several former Attorneys General of Canada. I have listed, in Appendix B, the people with whom we consulted. We were particularly assisted in these consultations by Professor Kent Roach from the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, and Dean Adam Dodek from the University of Ottawa Faculty of Law. Each of them generously co-hosted with me a roundtable of experts at their law schools. These were day-long events, during which we had animated discussions about the role of the Attorney General, the meaning and importance of prosecutorial independence and the rule of law, the potential for conflicts and interference, the history of efforts to protect against interference, and the implications of additional structural change on the function and efficiency of government departments. These roundtables greatly assisted me in understanding the factors I should consider when making my recommendations.

To understand how other countries have balanced the principles of independence and accountability, I reviewed international literature on the subject and spoke with a number of experts in other jurisdictions. Professor Philip C. Stenning, one of the foremost experts on Canadian and international approaches to protecting prosecutorial independence, spoke with us several times. The Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and her staff also kindly arranged a number of conversations with officials from the United Kingdom and Australia.

I also note that I told everyone with whom I consulted that the “Chatham House Rule” applied, to encourage them to speak freely.[3] That means that I will not attribute any particular view to any person, unless that person has given me specific permission to do so.

My team and I also conducted a thorough review of the academic literature and case law in Canada on issues relevant to my mandate. Appendix C lists the papers, books, legislation and guides we reviewed.

I benefited greatly from these various sources of information. However, the views and recommendations expressed in this report are mine alone.

The current Canadian framework

Democracies around the world have taken different approaches to reconcile the independence of prosecutorial decision-making with political accountability. Professor John Edwards, a Canadian professor who was the leading scholar on the role of the attorney general, noted that there are a “bewildering number” of approaches to defining the roles of the Attorney General, Justice Minister, and Director of Public Prosecutions (where that office exists).[4] Professor Edwards suggested that the differences in approaches reflect the “political aspirations, experience and attachment to democratic ideals” of each country and that these differences underscore the dangers of seeking a simplistic solution to real or perceived problems with the administration of justice in Canada.[5]

The roles of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

The Minister holding the position of Minister of Justice has always held the position of Attorney General of Canada, and has always been a member of Cabinet. Equally, the federal office holder has always had legal training, and I believe that it is important to continue this tradition.

Although the two positions are frequently referred to as a fused or joined position, it is more accurate to say that they are two separate positions held by one person.

Both positions have been described as being responsible for promoting and protecting the rule of law.[6] The Supreme Court of Canada has explained the rule of law as promising to citizens and residents “a stable, predictable and ordered society” where individuals are protected from arbitrary state action.[7] This means that the state can only use its power against individuals according to law. The rule of law also requires the state to be accountable to the public for how it uses those powers.

There are some responsibilities which clearly belong with the Minister of Justice, and others which clearly belong with the Attorney General. However, during my consultations there were differences of opinion on which function related to which role – Attorney General of Canada or Minister of Justice. Justice policy development falls to the Minister of Justice, while conducting litigation is the responsibility of the Attorney General of Canada. However, other responsibilities traditionally thought of as belonging to the Attorney General of Canada, including giving legal advice to Cabinet and giving advice on whether particular government actions or proposed legislation comply with the Charter, are in fact the responsibility of the Minister of Justice under the Department of Justice Act.

The Attorney General of Canada

The position of Attorney General originated many centuries ago in England, and was responsible for representing the King in legal proceedings. For that reason, the Attorney General is often referred to as the Chief Law Officer of the Crown.[8]

The Attorney General is responsible for providing legal advice to government and for conducting civil litigation. An essential part of the portfolio of the Attorney General of Canada is the oversight of the federal prosecution function. I will speak in more detail about that function below.

In their role of Chief Law Officer of the Crown, the Attorney General is not accountable to a particular government. They are required to act according to the law and the broader public interest, not according to personal or partisan interests.

The definition of ‘partisan interest’ is important. Professor Edwards describes partisan interests as follows:

Partisan considerations are anything savouring of personal advancement or sympathy felt by the Attorney General towards a political colleague or which relates to the political fortunes of his party or his government in power.[9]

Non-partisan interests include “the maintenance of harmonious international relations between states, the reduction of strife between ethnic groups, the maintenance of industrial peace, and generally the interests of the public at large….”[10] They involve the wider interests of the public, and go beyond any single political group.

The definition of “public interest” is context-specific. The Deskbook of the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC), which is the manual for federal prosecutors, includes examples of public interest considerations such as the impact on victims and the nature of the harm caused by the alleged crime.[11] The broader public interest can also include the impact of a prosecution on international relations or national security. There is no single definition of the public interest, as it will depend on the context of the individual case.[12] As Baroness Hale of Richmond said in R (Corner House Research) v. Director of the Serious Fraud Office, “The ‘public interest’ is often invoked but not susceptible of precise definition. It must mean something important to the public as a whole, rather than just a private individual.”[13]

I note Professor Stenning’s comment that “however superficially attractive and straightforward this distinction [between partisan and public interests] may appear, in practice it may not be easily applied to particular situations.”[14] This is because, in many instances, the approach that is taken may benefit the public while also serving partisan interests. Public opinion will be the final arbiter of whether the primary motivation is non-partisan.

Former Attorney General of Ontario Roy McMurtry said that Attorneys General, above all, are “servants of the law, responsible for protecting and enhancing the fair and impartial administration of justice, for safeguarding civil rights and maintaining the rule of law.”[15]

Another former Attorney General of Ontario, Ian Scott, emphasized that the Attorney General role – that is, the obligation to uphold the rule of law – always comes first:

[T]he Attorney General is first and foremost the chief law officer of the Crown, and … the powers and duties of that office take precedence over any others that may derive from his additional role as minister of justice and member of Cabinet.[16]

Moreover, the Attorney General’s personal character is of great importance. In my consultations, the personal integrity of the Attorney General was consistently identified as being vital to the role. This means that the Attorney General must be fearless in providing legal advice, no matter what the consequences. Professor Edwards noted that the character of the Attorney General is also essential to protect against partisan interference:

Based on my examination of the administration of justice in a broad sample of Commonwealth countries… I am convinced that, no matter how entrenched constitutional safeguards may be, in the final analysis it is the strength of character, personal integrity and depth of commitment to the principles of independence and the impartial representation of the public interest, on the part of the holders of the office of Attorney General, which is of supreme importance.[17]

The Minister of Justice

Under the Department of Justice Act, the Minister of Justice is the legal advisor to the Governor General, which means, in practice, that they are the legal advisor to Cabinet.[18] In addition, the Minister of Justice is responsible for the development of justice policy.

The Minister of Justice is also the administrative head of the Department of Justice Canada. The organization chart of the Department of Justice is set out at Appendix D.

The Department of Justice has the mandate to support the dual roles of the Minister of Justice and the Attorney General of Canada. It is responsible for justice policy development, such as Indigenous legal policy, criminal justice reform, family law and access to justice, to name a few. It is also responsible for drafting laws and regulations, conducting litigation, providing legal advice to other departments, and international issues such as extradition and mutual legal assistance.

The Minister of Justice is also responsible for a number of independent officers and justice-related agencies, such as the Privacy Commissioner and the Canadian Human Rights Commission.[19] The Minister is also responsible for recommending judicial appointments.

In 1985, the Department of Justice Act was amended to give the Minister of Justice the responsibility for reviewing government bills for inconsistency with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and reporting any such inconsistency to the House of Commons.[20] The Department of Justice also provides Parliament with statements explaining why a proposed bill complies with the Charter.[21]

The Minister of Justice can be seen as having obligations that are different from those of other Cabinet ministers. As the Department of Justice Minister’s transition book notes, the responsibilities of the Minister of Justice require them to “exercise their political judgment as a member of Cabinet, except when providing legal advice which must be independent and non-partisan.”[22]

The Attorney General and the Public Prosecution Service of Canada

The Attorney General of Canada is responsible for federal criminal prosecutions.[23] The power to prosecute is delegated from the Attorney General to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), the head of the PPSC. The Supreme Court of Canada has described the Attorney General’s role with respect to prosecutions as reflecting the community’s interest to “see that justice is properly done… not only to protect the public, but also to honour and express the community’s sense of justice.”[24]

The vast majority of offences under the Criminal Code are prosecuted by provincial governments. Many federal prosecutions are under federal criminal regulatory statutes such as the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, the Income Tax Act, the Competition Act and the Fisheries Act. There is also shared jurisdiction with the provinces for prosecuting certain Criminal Code offences, such as terrorism, organized crime and money laundering. The PPSC prosecutes Criminal Code offences on behalf of the territorial governments of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon.[25]

Prosecutorial independence

Although the police typically lay criminal charges, prosecutors have the power to withdraw, defer or change them. They also decide what sentence to recommend to the judge when a conviction is obtained. Although the exact tests vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, federal prosecutors can only proceed with charges after answering two questions. The first question is: based on the evidence, is there a reasonable prospect of conviction? If the prosecutor is of the opinion that the answer is yes, they must ask a second question: is it in the public interest to prosecute? A reasonable prospect of conviction alone does not mean a prosecution will proceed.

This power to make decisions about prosecutions, which is referred to as “prosecutorial discretion,” carries with it profound responsibility. As the Ontario Crown Prosecution Manual notes,[26]

Deciding to continue or terminate a prosecution can be one of the most difficult decisions a Prosecutor can make. The Prosecutor must act with objectivity, independence and fairness in each case to ensure a principled decision is made. It requires a balancing of competing interests including the interests of the public, the accused and the victim.

Because the prosecutor is required to make decisions fairly, objectively, and according to legal rules, prosecution decisions are often referred to as “quasi-judicial.” These decisions enjoy significant deference from judicial review.[27]

Attorneys General in Canada have the power to overrule decisions of prosecutors, which in practice they have only exercised in exceptional circumstances. Like prosecutors, Attorneys General exercise quasi-judicial functions when they make decisions about prosecutions.[28] This requires that they make those decisions independently.

The Supreme Court has described this principle of prosecutorial independence as a constitutional principle:

The gravity of the power to bring, manage and terminate prosecutions which lies at the heart of the Attorney General’s role has given rise to an expectation that he or she will be in this respect fully independent from the political pressures of the government.…

It is a constitutional principle in this country that the Attorney General must act independently of partisan concerns when supervising prosecutorial decisions.[29]

In countries where this prosecutorial independence is not respected, the police and prosecutors can be directed or pressured to prosecute the political enemies of the government, or to stop prosecutions of the government’s friends.[30]

The most commonly-cited source on how to give effect to the principle of independence of the Attorney General is the statement by Sir Hartley Shawcross, who was the Attorney General of England and Wales, in 1951:

I think the true doctrine is that it is the duty of an Attorney-General, in deciding whether or not to authorize the prosecution, to acquaint himself with all the relevant facts, including, for instance, the effect which the prosecution, successful or unsuccessful as the case may be, would have upon public morale and order, and with any other considerations affecting public policy.

In order so to inform himself, he may, although I do not think he is obliged to, consult with any of his colleagues in the Government; and indeed, as Lord Simon once said, he would in some cases be a fool if he did not. On the other hand, the assistance of his colleagues is confined to informing him of particular considerations, which might affect his own decision, and does not consist, and must not consist, in telling him what that decision ought to be. The responsibility for the eventual decision rests with the Attorney-General, and he is not to be put, and is not put, under pressure by his colleagues in the matter.

Nor, of course, can the Attorney-General shift his responsibility for making the decision on to the shoulders of his colleagues. If political considerations which, in the broad sense that I have indicated, affect government in the abstract arise, it is the Attorney-General, applying his judicial mind, who has to be the sole judge of those considerations.[31]

Justice Marc Rosenberg has explained the “Shawcross Doctrine,” as it is now known, in the following terms:

First, the Attorney General must take into account all relevant facts, including the effect of a successful or unsuccessful prosecution on public morale and order — we would probably now call this the public interest. Second, the Attorney General is not obliged to consult with cabinet colleagues but is entitled to do so. Third, any assistance from cabinet colleagues is confined to giving advice, not directions. Fourth, responsibility for the decision is that of the Attorney General alone; the government is not to put pressure on him or her. Fifth, and equally, the Attorney General cannot shift responsibility for the decision to the cabinet.[32]

As former Attorney General of Canada Ron Basford explained in 1978, the Attorney General should ensure that considerations based on narrow, partisan views, or based on the political consequences to the Attorney General or others, are excluded.[33]

This principle has been accepted by federal and provincial Attorneys General. It has also been supported in the case law and in numerous articles on the role of the Attorney General in criminal prosecutions.[34]

Accountability

The other key principle which comes into play when considering the role of the Attorney General is accountability.[35] In a democracy, members of government who exercise state power must be accountable to the public for their actions. Because prosecutors have such wide discretion, public confidence in the justice system requires that they be held accountable for the exercise of that discretion.[36]

This accountability comes in a number of forms. First, the DPP is accountable to the Attorney General. A second accountability is that of the Attorney General to the public through Parliament.[37] Professor Edwards described this political accountability as being as important as the principle of prosecutorial independence.[38]

Policy decisions made by the government are considered to be the collective responsibility of all members of Cabinet. However, because the Attorney General’s decisions in specific prosecutions are made independently and by the Attorney General alone, accountability for these decisions is personal.

Accountability is required in order to protect the democratic right of citizens to decide whether the powers of the state are being properly exercised. But accountability also serves to protect and promote prosecutorial independence. Attorneys General are less likely to make decisions for partisan reasons if they have to account for those decisions publicly. Nor are they likely to abuse that independence by making prosecutorial decisions for personal gain or other improper purposes.

Justice Rosenberg noted that the principles of prosecutorial independence and accountability “are crucial to the proper functioning of the administration of justice,” but are not always properly understood, even by members of Cabinet.[39]

Prosecutorial independence in practice

Historically, Canada has preserved the independence of prosecutorial decision-making through mutually-reinforcing principles, conventions, institutional arrangements, written guides, and norms of behaviour.

First and most important, of course, is the constitutional principle that prosecutors, including the Attorney General, are independent and must be free from partisan political interference or direction.

Second, virtually all prosecutorial decisions are made either by individual Crown attorneys or by their superiors in the prosecution service. It is highly exceptional for the Attorney General to be involved in prosecutorial decisions. This protects the independence of prosecutorial decision-making, but also protects the Attorney General from accusations of improper interference.

Independence is also protected by an administrative convention, where senior officials shield individual prosecutors from interference by the Attorney General or political staff.[40] Justice Rosenberg suggested that this convention “may be as important as any constitutional convention on the independence of prosecutions from improper partisan influences.”[41]

In the federal context, the PPSC Deskbook explains in detail the principles of prosecutorial independence, the accountability of the Attorney General, and the institutional and administrative mechanisms by which these principles are preserved. Federal prosecutors are required to follow the policies in the Deskbook.[42]

I have interviewed most of those who have occupied the position of Attorney General of Canada over the past 25 years,[43] and many former and current heads of prosecution services for Canada and the provinces. There was a broad consensus that prosecution decisions have been made independently. Former Attorneys General all agreed that it was not appropriate for them to overrule the heads of prosecution in individual cases unless there were exceptional circumstances.

The Director of Public Prosecutions Act

In 2006, the federal government made an important structural change to the federal prosecution system with the enactment of the Director of Public Prosecutions Act (DPP Act).[44] This Act was inspired by similar legislation in Nova Scotia, Québec, British Columbia, and Australia.[45]

The Minister of Justice at the time, the Honourable Vic Toews, explained the rationale behind the legislation in the following terms:

The idea behind this bill is… to ensure not only that prosecutorial decisions are untainted by partisan concerns, but to ensure that they are manifestly and undoubtedly seen to be untainted.

We do not suggest that prosecutorial independence at the federal level has been violated. The men and women who constitute the Federal Prosecution Service have been faithful guardians of prosecutorial independence. We are not here to correct a problem that has already occurred; we are here to prevent problems from arising in the future. That course of action seems to be more prudent, and we are here to assure Canadians that the Federal Prosecution Service is independent.[46]

The Act removed the federal criminal prosecution service from the Department of Justice and established it as an independent agency, headed by the DPP. The DPP has the rank of a deputy minister. The DPP is appointed on the recommendation of a selection committee made up of representatives of the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, each recognized political party in the House of Commons, the Deputy Minister of Justice, the Deputy Minister of the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, and a person selected by the Attorney General.[47]

The DPP is appointed for a seven-year period, and cannot be re-appointed. This is an important safeguard that enables the DPP to resist any improper interference.[48]

It is difficult, but not impossible, to remove the DPP. The DPP can only be removed for cause, and the majority of the House of Commons must support the removal.[49] (The Québec statute requires a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly to remove their head of the prosecution service.)[50] Even a government with a majority would face significant public attention if there was an any attempt to remove the DPP, so it would be unlikely to do so absent clear incompetence, impropriety or disability.

The DPP will issue guidelines to federal prosecutors regarding the general conduct of prosecutions, give advice to investigative agencies such as the RCMP, and communicate with the media and public about federal prosecutions.

The prosecutors in the federal prosecution service report to the DPP, who has the authority to hire, fire, and discipline them. The DPP can also hire outside lawyers to conduct prosecutions and experts, without the approval of the Attorney General. The DPP is required to submit an annual report to the Attorney General, which is tabled in Parliament.

Section 13 notices

Section 13 of the DPP Act requires the DPP to send a notice to the Attorney General that it intends to prosecute or intervene on a matter “that raises important questions of general interest.”[51] These notices serve two purposes. First, they provide the Attorney General with information on cases of significance. Secondly, having this information enables the Attorney General to decide whether to exercise their authority to become involved in the prosecution.

Kathleen Roussel, the current Director of Public Prosecutions, told me that she sent 62 of these notices in 2018. The DPP also sends more informal memos about cases which may not meet the “general interest” standard but where, for example, there is the possibility that the Attorney General will be asked about the case in the House of Commons.

The Act does not have any rules about what information must be in these section 13 notices. Ms. Roussel told us that the notices are usually short, setting out the basic facts of the case, the decision being made, and the reasons why. On some files, the DPP will send several of these notes on the same case, at different stages of the prosecution.

I was also told that most section 13 notices do not prompt the Attorney General to take any further action. The Attorney General may nevertheless contact the DPP to learn more about the evidence in the case or the reasons for the decision the DPP has made. The Attorney General can ask the Deputy Minister of Justice for advice on their options and/or on the merits of the DPP’s position. If the Attorney General requests, the Deputy Minister may contact the DPP on their behalf. The Attorney General can, in their discretion, also seek a second opinion, either from the Department of Justice, or from an outside expert retained for that purpose.[52]

Section 13 notices are considered to be legally privileged documents, meaning that they normally are not disclosed to the accused.

There is no uniform approach in Canada or other jurisdictions as to how much, if any, communication there should be between the Attorney General and the DPP outside of these section 13 notices. Although the frequency and manner of communication may vary, those I consulted highlighted the importance of a relationship of trust between the Attorney General and the DPP.

Directives on specific prosecutions

The DPP Act permits the Attorney General to issue a directive to initiate, defer or terminate a specific prosecution. Any such direction must be in writing and published in the Canada Gazette.[53] The Attorney General or DPP is permitted to delay the publication of the directive where it is in the interest of the administration of justice, but not beyond the completion of the prosecution.[54] The law does not spell out what should be in the directive.

The Deskbook notes that this provision is one of the hallmarks of independence, since it requires transparency in the public domain which “serves as a strong deterrent against partisan political influence and pressure in prosecution-related decision-making.”[55]

In my consultations, I was told consistently that this transparency is important. It makes clear that the Attorney General would have to be prepared to account to the public for a decision to overrule the DPP.

The directive requirement does not prevent an Attorney General and DPP from discussing the DPP’s decision. These discussions could involve new facts or public interest considerations, and might lead the DPP, of their own accord, to reconsider.[56]

Directives on a specific prosecution are rare in those Canadian and Commonwealth jurisdictions which provide for them.[57] No Attorney General of Canada has issued a directive in a specific case since the DPP Act was passed in 2006. This suggests that the culture of non-interference by the Attorney General that was established prior to 2006 continues.

Taking conduct of a prosecution

The DPP Act allows the Attorney General to assume the conduct of a prosecution (typically by hiring an outside agent to conduct the prosecution on their behalf). The Attorney General cannot take this step without consulting with the DPP, and must give the DPP notice of intent to assume conduct of the prosecution.[58] As with specific directives, the notice must be published in the Canada Gazette and the Attorney General or DPP may delay publication of this notice if it is “in the interest of the administration of justice”.[59] This is arguably the most significant power of the Attorney General in the DPP Act, but it has never been used in any jurisdiction in Canada where a statutory DPP exists.

General directives

The DPP Act allows the Attorney General, after consulting with the Director of Public Prosecutions, to issue directives relating to the initiation or conduct of prosecutions generally.[60] They, too, must be in writing and published in the Canada Gazette, and form part of the Deskbook.

Those with whom I consulted were of the view that this directive power is a positive tool for helping prosecutors determine the public interest. It can be used to articulate government criminal law priorities, highlight the importance of adherence to court rulings, and explain the government’s interpretation of legislation. Directives have been issued at the federal level on terrorism prosecutions, HIV prosecutions, wrongful convictions, and the conduct of prosecutions generally.[61]

Evaluating the current model

Professor Edwards described six different models related to the structure and role of the Attorney General.[62] These can be broadly grouped into three categories. In some jurisdictions, the person with ultimate authority over prosecution decisions is a public servant. There is no mechanism for elected officials to override their decision on any specific prosecution, and it is difficult to remove them from office.

In other jurisdictions, the person with ultimate authority for prosecutions is a politician, is a member of Cabinet, and can intervene[63] in any prosecution. Canadian jurisdictions fall within this model. Most give the portfolios of Minister of Justice and Attorney General to the same person.

A third model is the approach taken in England and Wales, where the Attorney General is a minister but does not sit in Cabinet. Further, since 2009, the Attorney General of England and Wales may issue a direction to prosecutors only on the ground of national security.[64]

Professor Stenning thoughtfully prepared for us a memo explaining the functions, characteristics and authority over prosecutions of Attorneys General in common law countries, which complements and updates Professor Edwards’ six models. I have attached this memo as Appendix E.

Given the context that gave rise to my mandate, I will focus my analysis on the Attorney General’s criminal prosecution role. I did hear suggestions about the roles of the Minister of Justice and Attorney General in relation to non-prosecutorial matters, which I will address separately.

Suggestions for structural change with respect to the prosecution function

Critics of the current structure in Canada have suggested that reform is needed for the following reasons:

- It is unrealistic to think that an Attorney General who is also the minister responsible for justice policy can exercise independent judgment when making decisions about specific prosecutions.

- The fact that the two roles are held by one person can cause confusion on what issues it is permissible to discuss with that person.

The suggested reform to address these first two concerns is to assign each role to a separate Cabinet minister. - Even if the roles were held by two different people, as long as the Attorney General is in Cabinet, they might be influenced to exercise their authority in specific prosecutions so as to promote Cabinet’s policy agenda and/or improve the electoral prospects of the government.

The reform suggested is to remove the Attorney General from Cabinet. - Some argue that as long as the person with final authority over specific prosecutions is a politician, there is a risk that they will make decisions based on partisan concerns.

The reform suggested is to remove the Attorney General’s power to issue directives in individual cases, and leave final authority with an appointed official. Alternatively, the Attorney General could be a non-political appointment.

The perception by the public that a conflict exists is an important consideration, even absent actual conflict. Justice must not only be done, it must be seen to be done. However, in my view, engaging in structural change for that reason alone could create a false sense of security among the public while failing to alleviate the risk of prosecutorial interference. It also might lessen public vigilance and demands for accountability that are essential to a well-functioning democracy and the protection of the rule of law.

Let me address another argument I heard. I do not find workload to be a convincing argument for assigning the roles to separate people. None of the former Attorneys General I consulted identified workload as a concern that would justify a separation of the roles. More than one former Attorney General commented that their workload in other portfolios was more onerous.

Concerns arising from having one person hold the roles of Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

Conflict

The concern here is that the person holding the joined Attorney General - Minister of Justice roles may be tempted to direct a specific prosecution in order to further justice policy goals. For example, a justice minister in a government that wanted to appear tough on terrorism might be tempted to overrule a DPP decision to withdraw a terrorism-related charge, even in the absence of evidence to support the charge.

It would be highly unlikely for a minister to do this in a specific case. The DPP Act would require this to be done in an open and transparent manner, and this power has never been used since the creation of the DPP. Its use would bring a high degree of public and political scrutiny. This safeguard would act as a significant disincentive to stray from the longstanding practice of non-interference by the Attorney General in prosecutorial decisions. Moreover, a separate Attorney General who is an elected member of the government would not be immune from public anxiety about terrorism.

In my consultations, the notion that an Attorney General would not be able to act independently in the exercise of their prosecutorial authority because of their additional role as Minister of Justice was not of concern. The vast majority of those to whom I spoke did not raise the joined roles as an impediment to an independent prosecution, and in the words of several people, splitting the roles for this reason was a “solution in search of a problem.”

Assigning the two roles to separate ministers would not reduce the potential for conflict in the prosecutorial context in any appreciable way. It would also leave the person with policy-making responsibilities for the justice system without the broad perspective over the criminal justice system that the combined roles provide.

Confusion

It has been suggested that the joined Attorney General and Minister of Justice roles can create confusion among members of Cabinet and officials. In addition, some Cabinet colleagues and officials may believe that because the Attorney General is a Cabinet minister, they are able to discuss partisan concerns with respect to a specific prosecution. I believe any such confusion derives from a lack of understanding of the role of the Attorney General as an independent decision maker in criminal prosecutions.

In my opinion, the potential exists for confusion as long as the Attorney General is at the Cabinet table, whether or not they have responsibilities as Minister of Justice. As a result, I will deal with this concern in the following section.

Concerns arising from membership in Cabinet

Conflict

Removal of the Attorney General from Cabinet membership has been suggested because of a fear that the Attorney General might be influenced by Cabinet conversations about specific prosecutions.

In order for this risk to result in an inappropriate overruling of the DPP, the constitutional principle that the Attorney General cannot act based on partisan considerations would have to be breached. In addition, colleagues would have to be speaking in Cabinet about a specific prosecution, which is not permitted. Finally, the Attorney General would do so knowing that the directive overruling the DPP would be made public and that they would have to account for it.

Again, I believe this risk is minimal. Moreover, I do not think that removing the Attorney General from Cabinet would insulate them from such influence. I learned in our consultations that in recent years, Attorneys General in England and Wales, although not members of Cabinet, regularly sit in Cabinet meetings. This development has been explained as resulting from the fact that many government policies raise legal issues. As the legal advisor to Cabinet, the Attorney General can be more effective if they are present to identify and respond to legal issues as they arise.

The second source of possible conflict is that, in spite of knowing about the conventions and rules, members of Cabinet or the Prime Minister might nevertheless direct or pressure the Attorney General to overrule the DPP.

In this situation, the integrity of the Attorney General becomes critical. The Attorney General is required to remind their colleagues that this is constitutionally impermissible, and resist.

Removing the Attorney General from Cabinet would not remove the risk of pressure or direction from the Prime Minister or other members of Cabinet. I agree with those who have argued that as long as the Attorney General serves at the pleasure of the Prime Minister, there is potential for pressure or direction.

This reality has been illustrated by events in England and Wales over the past two decades, where concerns were raised about the independence of the Attorney General, notwithstanding his exclusion from Cabinet. In one case, these concerns and other concerns led to the seven-year long Chilcot Inquiry.[65]

The Chilcot Inquiry involved the government’s decision to go to war with Iraq in 2003. The then-Attorney General, Lord Goldsmith, initially provided a legal opinion that prevented the UK from joining coalition forces. After receiving representations, he changed his opinion. Critics believed he had been swayed not by legal argument, but by pressure from the Prime Minister who had appointed him, Tony Blair.[66]

Then in 2006, an investigation into BAE Systems Plc with respect to corruption involving arms trading with Saudi Arabia, was terminated following communications between the Attorney General and others, including the Prime Minister. There were suggestions that the Attorney General and Director of the Serious Fraud Office had succumbed to political pressure to end the investigation.[67] This led to litigation and a decision by the House of Lords that the Serious Fraud Office had acted lawfully.[68]

Without suggesting that the Attorney General did act in a partisan fashion, in each of these cases, the Attorney General’s exclusion from Cabinet was not sufficient to remove the perception among some members of the public of inappropriate pressure.

The experience in England and Wales demonstrates that removing the Attorney General of Canada from Cabinet would not insulate them from the possibility of actual or perceived interference. I heard from a number of people that this is the real source of potential interference: the Attorney General depends on the Prime Minister for their position as a minister and as a candidate for re-election.[69]

The creation of the DPP has also gone a long way toward mitigating the concerns over the Attorney General’s presence in Cabinet. The Law Reform Commission of Canada noted in 1990 that removal of the Attorney General of Canada from Cabinet could in theory promote prosecutorial independence, but concluded that “what is most important is a clear understanding of, and adherence to, the principle of non-partisanship by the decision-maker.”[70] The Commission did not recommend removal from Cabinet, but did recommend the creation of the DPP.[71]

Concerns arising from a political Attorney General

The reality is that the possibility of interference with prosecutorial decisions cannot be eliminated altogether, as long as the person with ultimate control over prosecutions is a politician. I believe that this is the real source of concerns about both the real and perceived independence of prosecutorial decision-making.

Another option for structural change, then, would be to remove this role from the political sphere altogether. This could be done by making the Attorney General an appointed, non-political official, who has tenure beyond the life of a particular government, and who cannot be directed by a member of the Executive. This is similar to the approach in Israel.[72]

The simpler option, given that we already have a DPP with most of those characteristics, would be to amend the DPP Act to remove the power of the Attorney General to take over prosecutions or issue specific directives.

This approach was endorsed recently by Professors Martine Valois and Maxime St. Hilaire:

Prosecutorial independence is a recognized constitutional principle in Canada. But its implementation leaves much to be desired. In our respectful view, Canada should bring its practice into better harmony with global standards by repealing ss. 10(1) and 15 of the Director of Public Prosecutions Act. Doing so would return the Attorney General to her proper role as a legal advisor to the government and a minister of the Crown and would establish a bright line between those who counsel the government on legal matters and those who conduct criminal prosecutions. The principle of prosecutorial independence, and, indeed, the rule of law itself demand that these roles remain more clearly separate and distinct.[73]

Each of these approaches removes any ability of an elected official to overturn the decision of the DPP. This has the effect of leaving decisions with significant implications for the public interest to an unelected official.[74] As one former Attorney General of England and Wales told me, the greater the implications for the public interest, the more important it is that an elected official carry the responsibility for that decision.

I agree with the conclusions of the Law Reform Commission in 1990 that leaving the Attorney General with some residual power to direct the DPP is preferable to removing their power altogether, as it avoids leaving the office of the Attorney General as “an empty shell, ‘incapable of discharging in full the obligations associated with the doctrine of ministerial responsibility.’”[75]

Secondly, a DPP who is, as Professor Kent Roach explained “politically insulated …may make prosecutorial decisions without the necessary information about the broader effect of such decisions, for example, on foreign and domestic intelligence agencies.”[76] Professor Roach goes on to note the difficulties involved in having the DPP, rather than the Attorney General, responsible for receiving representations from Cabinet ministers regarding the public interest:

If the DPP is so informed, however, there is also a danger that the DPP will not be in the same position as the AG (who sits in Cabinet in Canada or who attends Cabinet as in the United Kingdom) to probe, question and follow up on information provided by relevant Ministers and Ministries. Perversely, an insulated and protected DPP may be more vulnerable than an AG to exaggerated claims that a prosecution would threaten national interests.[77]

Another option could be to maintain the Attorney General’s authority to issue directives, but to severely restrict it. In England and Wales, that authority is limited to national security matters. I believe there are legitimate reasons for retaining the Attorney General’s residual power to intervene beyond national security.[78] One can imagine situations where delicate international negotiations could be negatively affected by a prosecution. Moreover, prosecutors can make improper decisions based on tunnel vision,[79] racism,[80] or stereotypes about either the accused or victims.[81] This is rare, but possible. In my view, severely restricting or removing the Attorney General’s authority to intervene in prosecutions would not be an appropriate way to reduce pressure.

Conclusion on proposed structural changes with respect to the prosecution function

It has become clear to me that there is no system for managing prosecutorial decisions which absolutely protects against the possibility of political interference in specific prosecutions, while providing for public accountability. Professor Edwards’ research showed that decisions about prosecutions can be made subject to inappropriate pressure under any model.[82]

The Law Reform Commission made a similar point:

Systems that incorporate an extreme degree of institutional independence, as well as those with virtually no structural independence, both seem to be capable of producing an apparently unbiased prosecution service. It can be argued that what is crucial, therefore, are not the institutional arrangements, but rather adherence to the proper governing principles.[83]

In the end, I do not believe that further structural change is required in Canada to protect prosecutorial independence and promote public confidence in the criminal justice system. Legislation, education, protocols, cultural norms, transparency and constitutional conventions all have a role to play and have been effective to date. The DPP Act provides strong structural protections against political interference. The personal integrity of the Attorney General is also essential; indeed, it is probably the most important element in a system which protects the rule of law.

The model of having the same person hold the Minister of Justice and Attorney General roles was deliberately chosen at Confederation, and for good reason. Our system benefits from giving one person responsibility for key elements of the justice system. Joinder of the two roles creates important synergies. That person gains a perspective over the entire system which could not be achieved if the roles were divided; so too do the lawyers and policy experts who work together in the Department of Justice.

Removing the Attorney General from Cabinet would also affect the credibility and quality of legal advice they provide. In my view, Cabinet colleagues are more likely to pay attention to the Attorney General’s legal advice because they know that the Attorney General, as a member of Cabinet, understands the political context in which they are operating. That advice is also likely to be better informed, and therefore more helpful to Cabinet.

Suggestions for change outside the prosecution function

Although most of my consultations concerned the independence of the criminal prosecution function, there was discussion about the independence of the Attorney General in non-prosecutorial matters. This includes giving legal advice to Cabinet, non-criminal litigation and identifying legislation which does not comply with the Charter.

There is a distinction between the independence of the Attorney General in prosecutions as a decision-maker with personal accountability, and the independence of the Attorney General as a legal advisor and provider of legal services. This second type of independence is not absolute. Cabinet is free to disregard the Attorney General’s advice, although as former English Attorney General S. C. Silkin stated, this should not be done lightly:[84]

It is the duty of the Law Officers of the Crown to advise their fellow Ministers and government departments both as to the law and as to the constitutional proprieties. They are responsible for recommending to their colleagues what can properly be done within the law and what can not. The decisions are those of their colleagues. But they will not lightly ignore the advice of the Law Officers upon matters falling within the Law Officers’ responsibility.

This is especially true in the Charter era, where constitutional considerations are such an important part of the development of policy.

There are several concerns about conflict of interest and independence in the non-prosecutorial sphere. As Dean Dodek has written, there is a concern that the person who is responsible for developing policy proposals in the justice area will not be able to give Cabinet an unbiased assessment of the legal risk associated with those same policies.[85] There is a similar concern that an Attorney General will not be able to provide fearless legal advice to their Cabinet colleagues on the overall government policy agenda. The crux of this argument is that it is unrealistic to think that a partisan politician can split their mind to provide the best independent and non-partisan advice.[86]

I have listened carefully to these concerns.

I do not believe that the challenge of designing a new organization to respond to these concerns is impossible. Although there are grey areas of responsibility in the Department of Justice Act, these could be clarified through new legislation. For example, the Minister of Justice could be given responsibilities for justice policies, including criminal and family law reform, human rights and access to justice, as well as responsibilities for recommending judicial appointments and managing the broader justice portfolio.[87] All of the services provided by Department lawyers to other departments, litigation, and perhaps even legislative and regulatory drafting, could be the responsibility of the Attorney General.[88] The Attorney General would head their own government department but would have no policy role in government. They could be a member of Cabinet, or we could follow the British model where the Attorney General is not a member of Cabinet but is invited to attend as needed.[89]

Just because it is possible to divide the Department of Justice does not mean that we should. While not unanimous, the vast majority of those I consulted cautioned against changing the structure in the non-prosecution context. Those with direct experience in government were particularly concerned about the implications of such a change, especially because the organizational structure has always been integrated. As I noted earlier, such a structural change would diminish the credibility of the Attorney General’s legal advice and lead to the loss of the broad perspective the joined roles provide to the person holding them.

I therefore do not recommend a split of the department or removal of the Attorney General from Cabinet because of perceptions of conflict in the non-prosecutorial sphere. In my recommendations, however, I have set out changes that address some of the concerns arising in this context.

Should the government ever contemplate an organizational change, it should guard against unintended negative consequences. The following are some issues that should be considered:

- Is organizational change the optimal way to prevent potential conflicts of interest?

- Would organizational change reinforce a culture of respect for the role of the Attorney General in their non-prosecutorial role?

- What steps should be taken to ensure that justice policy proposed by the Minister of Justice and legal advice given by the Attorney General would have the same weight in Cabinet and in the government if the roles were separated?

- How would two smaller departments maintain sufficient influence to ensure that they receive adequate resources?

- What steps should be taken to mitigate the costs of organizational change, including the loss of synergies provided by the joint roles?

A proposed Canadian approach to the role of the Attorney General

My recommendations relate to two broad categories: providing more guidance on Ministerial consultations in specific prosecutions, and encouraging a greater understanding of, and respect for, the unique role of the Attorney General.

Enhancing the independence of the Attorney General in individual prosecutions

While I do not believe there is a need for structural reform, there are practical steps that should be taken to reinforce prosecutorial independence.

A protocol for Ministerial consultations on the public interest

The circumstances giving rise to my appointment as Special Advisor involved the propriety of communications by ministers, their political staff and the Clerk of the Privy Council with the Attorney General and her office with respect to a specific prosecution. This is reflected in the second question of my mandate.

As noted earlier, prosecutors initially determine, based on the evidence, whether there is a reasonable prospect of conviction and if so, whether there is a public interest in proceeding with the prosecution.

In determining the public interest, the DPP and prosecutors may decide to consult with officials in government departments and agencies that have information or expertise that may be relevant to specific prosecutions. Interdepartmental consultation is also important because of the shared responsibilities among government departments for enforcing federal laws. The policies governing federal prosecutors include a general directive from the Attorney General on consultation within government, issued in 2014. It states:

In some instances prosecutorial decision-making, including the determination of whether a prosecution best serves the public interest, whether charges should be stayed, or a particular position on sentence taken, may warrant consultation with those who can provide Crown counsel with relevant information and expertise.[90]

If the DPP is of the view that it would be advisable to have representations from ministers in order to ascertain the public interest, then they should make a request to the Attorney General. This process is contemplated in the United Kingdom protocol.[91]

From my consultations with former Attorneys General and current and former heads of prosecution services, it appears to be rare for Attorneys General of Canada to engage in consultations to determine the public interest in individual prosecutions. Almost invariably, such public interest consultations are instead conducted by the DPP. However, following the Shawcross Doctrine, Attorneys General may choose to consult with others, including other members of government, on the public interest when deciding whether to override a DPP decision. The principle of prosecutorial independence requires that these consultations not be used as a mechanism for intimidating or directing the Attorney General.

The practice of consultation by the Attorney General of Canada is recognized in the Cabinet manual, Open and Accountable Government, issued by the current government after it took office in late 2015:

The Attorney General and the DPP are bound by the constitutional principle that the prosecutorial function be exercised independently of partisan concerns. However, it is appropriate for the Attorney General to consult with Cabinet colleagues before exercising his or her powers under the DPP Act in respect of any criminal proceedings, in order to fully assess the public policy considerations relevant to specific prosecutorial decisions.[92]

The general directive issued to the prosecution service by the Attorney General in 2014 notes that “it is quite appropriate for the Attorney General to consult with Cabinet colleagues before exercising his or her powers under the DPP Act in respect of any criminal proceedings. Indeed, sometimes it will be important to do so in order to be cognizant of pan-government perspectives.”[93]

There is no reference in the DPP Act to the Attorney General’s ability to consult with other members of Cabinet.[94]

Perhaps because the Attorney General is so infrequently involved in public interest consultations, there is little guidance on how a ministerial consultation process should proceed. The statements by Lord Shawcross, Attorney General Basford and others on the subject discuss the right of the Attorney General to consult with other members of the Executive, but do not explain the proper process for such consultations. Indeed, as I heard a number of times in my own consultations, the Shawcross Doctrine does not answer the questions of who, what, when, where, and how these consultations ought to take place.

Without a protocol, there is no standard against which to measure the propriety of ministerial public interest consultations. I am of the view that public confidence in the justice system requires that the parameters of these consultations – rare though they may be – should not be determined on an ad hoc basis. It is time we updated the Shawcross Doctrine with a made-in-Canada approach.

Following the controversies in England and Wales to which I referred earlier, and the subsequent reviews of the role of the Attorney General there, a protocol was created in 2009. This protocol, which was amended in 2019,[95] includes rules to govern ministerial consultations on the public interest, and notes that they should be conducted “with propriety.”

I propose that we develop a protocol in Canada to govern consultations in specific prosecutions. A detailed protocol would give Canadians confidence that there are clear rules about how public interest consultations will be conducted.

The protocol would not prohibit vigorous discussions about where the public interest lies, but it would make clear that the final decision is that of the Attorney General alone. The Attorney General of Canada should develop a protocol that would apply to ministers, their staff, the Clerk of the Privy Council and the public service. These rules should cover the following issues:

- Who is entitled to initiate consultations;

- Who determines the process for such consultations;

- When and where the consultations take place;

- Who is entitled to be part of the consultation discussions;

- What the scope of the discussion should be; and

- The Attorney General’s options and obligations in response to such consultations.

The answers to these questions are up to the Attorney General to determine. In the normal course, the Attorney General would be the person responsible for determining whether consultations are needed. Other ministers should not be able to insert themselves into the decision-making process by demanding to consult with the Attorney General. The original statement of the Shawcross Doctrine implies that it is the Attorney General who decides whether or not to consult. This is consistent with the idea that there is no obligation to consult and the consultation only occurs where the Attorney General sees value in it.

However, I do believe there are some circumstances in which another minister may have information, not known to the Attorney General, which might be relevant to their decision as to the public interest in a specific prosecution. Therefore, in such cases, another minister may request the consultation. This was the process in the BAE case, even before the creation of the 2009 protocol. There were requests for consultations which were granted by the Attorney General.[96]

The Attorney General should have sufficient information to determine whether to conduct a consultation. Therefore, the minister requesting the consultation should provide a description of the nature of the representations to be made.

The Attorney General should determine the process. In most cases, the consultations should be done through written representations. This will discourage discussions of improper considerations. It will also enable the Attorney General to analyze the soundness of the representations being made. Written representations may need to be supplemented with in-person discussions, but there should be a written record of those discussions. In some cases, these records may need to be classified. Documenting these discussions would help the Attorney General to consider their merit, and reduce the risk of partisan suggestions. I heard from several experts including a former Attorney General of England and Wales that it is important to ensure that all such representations are documented and minuted.

The venue for these discussions should not be the Cabinet table. Cabinet has no role in individual prosecutions, and they should never be discussed at the Cabinet table. Former Attorney General of England and Wales Lord Anthony Goldsmith noted that in the BAE case, he deliberately did not entertain discussions of the public interest in Cabinet.[97] Further, a discussion in Cabinet may lead to the perception that the Attorney General will be either influenced by partisan considerations or subject to undue pressure. Only the minister or ministers with specific information on the public interest should be involved in these consultations, along with their deputies (who are likely to have the specific details relevant to the case). Keeping these discussions outside of the Cabinet room also underscores the fact that the Attorney General does not make decisions on the public interest as a member of Cabinet, but rather does so as the independent Chief Law Officer.

In my consultations with lawyers and leading authorities on the role of the Attorney General, there was a strong consensus that exempt political staff should not be involved in the substance of the consultations. I do not think it is necessary or advisable for them to be present during these consultations, which will take place rarely. I heard that in Ontario, for example, political staff are not invited to any discussions of a specific prosecution. In the final analysis, it is for the Attorney General to decide who should be present at these consultations.

The scope of the discussions should be confined to the effect of the prosecution on the public interest. Partisan concerns, such as the potential impact of a decision on the prosecution in question on the electoral future of the governing party, an individual MP, or the Attorney General, are not to be discussed. Nor should there be any discussion about the impact of such a decision on the Attorney General’s position in Cabinet, nor on their relationship with the Prime Minister or other members of Cabinet.

The statement of Lord Shawcross notes that the Attorney General should never be subject to direction or “pressure” during these consultations. Professor Edwards also notes that in order to protect independence, prosecutors, including the Attorney General, should not be subject to political pressure – that is, pressure to make decisions about specific cases for partisan purposes.[98] In my view, “pressure” here refers to threats, implied or explicit, that a decision by the Attorney General would result in a negative consequence for the Attorney General – for example, that their position in Cabinet or in the party could be at risk. Pressure could also come in the form of enticements or promises of a benefit. Persistence would also be a factor to be considered. The term “pressure” does not, however, refer to the kind of vigorous discussions between members of the government that is common and, indeed, desirable to understand fully the public interest.

Another way to consider the term “pressure” is to ask: would a reasonable person believe that the Attorney General might be influenced to change their position for reasons unrelated to the public interest as a result of a comment or suggestion, whether express or implied? Statements which would have that effect are not permissible during these consultations.

The final decision on the soundness of the representations and their implications for the public interest will be the Attorney General’s to make, alone. The Attorney General should scrutinize the information placed before them and test the soundness of the factual assertions and their relevance to the public interest. Given the complexity of the situations in which the protocol will likely be used, it is appropriate for the Attorney General, if they choose, to have further ministerial conversations. They can also speak with the DPP and/or Deputy Minister of Justice about the information they received in the consultations.